Theresa Whitehill’s poems tread a tenuous path at the boundaries between personal and collective reckonings with work that portrays grief, tenderness, defiance, and outrage. The result is a suite of fourteen poems that witness the almost unbearable pace of relentless crises of recent years—covid, climate change, racial injustice, the threat of totalitarianism, immigration crises—and begins to dwell in what might lie beyond these times.

“Whitehill subverts the forms of the lament and the ballad and the assumed lyricism that goes along with those forms, nearly lulling the reader into a seeming complacency, before tripping the reader up at a key moment to declare: “War then: the background always. Dreamers / and heretics—always.” — Inge Bruggeman, Foreword, The Heavy Lifting Companion

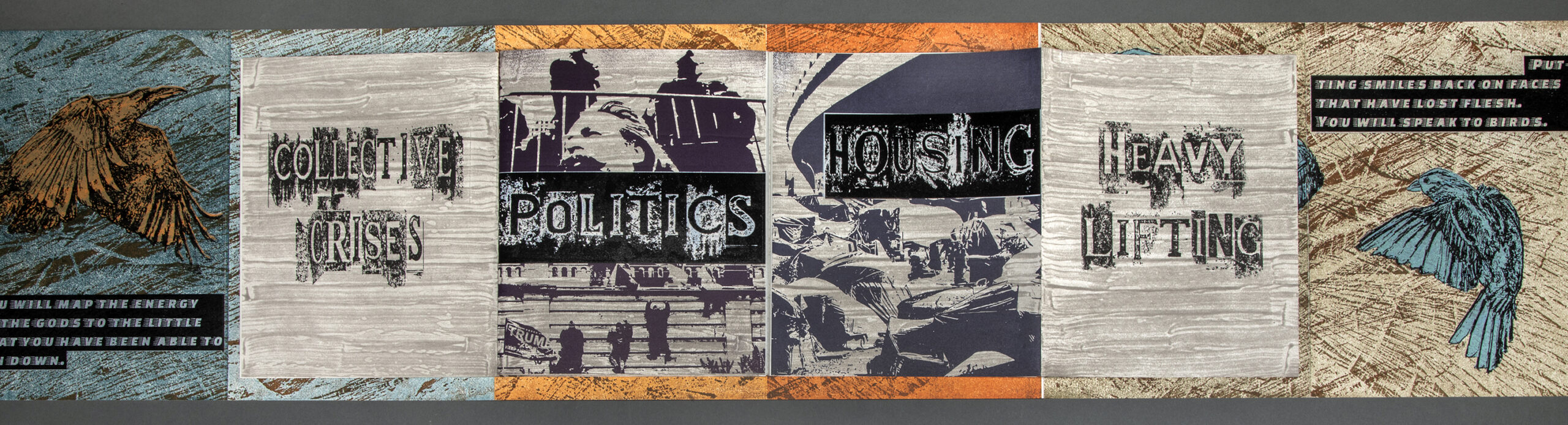

Many of the texts selected by Rice for the artists’ book are drawn from the poem of the same name. The title arose out of a volley of generative emails between Rice and Whitehill which are documented in “Genesis” in The Heavy Lifting Companion.

HEAVY LIFTING

This is the pause I am flying in, flying hard so as not to fall to earth.

Apparently, grief is not a calm, but a huge effort.

—letter from a friend

It’s hard to convey the crisis that happened to us

back in the early 21st century, the multiple crises,

the concatenation of disasters, the wounding,

the beginning of the ending of the wounding,

the unraveling of all that had gone before.

That we were already carrying the burden

of the dying off of the polar bears

and the failing of the glaciers, that was hard enough,

but it was when birds began to fall out of the sky—

emaciated, desperate, if not already dead,

that we realized.

We were no longer living in the time of prophecy,

no longer in the theory of it all. It was unfolding

all around us, one heart-stop after another,

a chain reaction of seemingly helpless events.

We had poisoned the well. And just because

we couldn’t conceive of it doesn’t mean that

it didn’t happen. It just means we couldn’t conceive

of it. Because the evidence, there it was—

looking up, the blue heron folded over on itself

heading south in the early sky. And north,

crossing paths—a helicopter.

From this time, we date a different life. The stories

we told our children changed at this time.

Our dreams changed. Some of us stopped dreaming.

Others registered guns or took part

in compromised immune systems.

War, then: the background always. Dreamers

and heretics—always.

And out of this arose a powerful and dangerous

tendency, a hiccup in history, a scratch in the record’s

fine vinyl grooves that caused it to skip and repeat

unerringly—so that while some of us were remembering,

were touching our faces to the glass, others were forgetting,

or not so much forgetting as to never have taken in those events

that were more than the consciousness could bear.

We lived in that nervous slice between forgetting

and the inevitable. This was the place we were brought to,

where we could stand and look out, and call out

to our children. This was the place where we lived

and where we ate and made love, amidst emergency vehicles

and fraud and the study of legal briefs, among our most sacred

texts that had become practically useless to us.

They were all on fire anyway.

Birds were at one time used as weapons of war.

They would be doused with flammable fluid and lit

on fire and sent into the enemy’s lines. Incendiary

birds could change the fate of battles.

Everywhere we went there was this upwelling

of the things of the earth—butterflies, yes, the leafing out

of the oak, the composition of new forms of music,

but also tombstones, defunct tractors, oil tankers run aground,

the bellies of salamanders, the windows

without glass.

We will make do with what we are given—a grammar

of what exists in which grief is a room locked up

within the emptiness of the sky. You who come after us

will carry the earth on your shoulders as birds carry the air

and are carried. Be lifted by these things that broke us.